-

Car Reviews

- All reviews

- Midsize SUVs

- Small cars

- Utes

- Small SUVs

- Large SUVs

- Large cars

- Sports SUVs

- Sports cars

- Vans

Latest reviews

- Car News

-

Car Comparisons

Latest comparisons

- Chasing Deals

Chasing Cars dives into the different types of induction found on many combustion-engined cars

When I buy a car, what does the dealer mean when they say the car is turbocharged or supercharged? What do car people mean when they say a car is naturally-aspirated?

In this guide, Chasing Cars will guide you through the common terms when it comes to the aspiration and forced induction of a vehicle’s engine.

When was the naturally-aspirated combustion engine invented?

There are various answers to this question.

The naturally-aspirated internal combustion engine was patented by Samuel Brown in 1823 for a gas-vacuum engine, however it was Nicholas Otto who invented the first four-cycle internal combustion engine. Otto went on to make, yep, the Otto engine that had the same four strokes used in modern engines today: intake, compression, power and exhaust.

How does natural aspiration work?

The basics of internal combustion revolve around atmospheric pressure. Think of the combustion engine as similar to a pair of lungs on a human being. Our bodies suck in the air for energy and then force the air out as exhaust, or in our case, carbon dioxide.

How this differs to force induction is that the engine is only taking in atmospheric air, rather than having air ‘forced’ into the cylinders by the means of a turbocharger or supercharger.

The engine naturally acts as a vacuum. If you put your hand over the snorkel of a four-wheel drive, for instance, you will feel your hand pull towards the outlet of the snorkel, which demonstrates how an engine creates its own vacuum.

Upsides and downsides of natural aspiration

The upsides of naturally-aspirated engines are that they are easier to maintain and less complex, are cheaper to produce and provide better throttle response.

The downsides are that efficiency and the power-to-weight ratio is decreased and the lack of forced induction provides less opportunity for tuning.

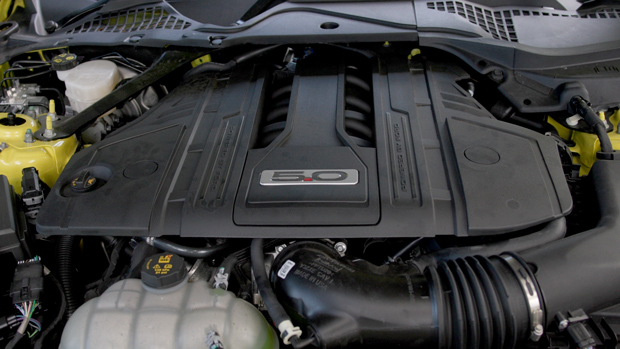

What cars use NA engines?

Despite the now widespread use of forced induction, there are many cars still on sale in Australia that are fitted with naturally-aspirated engines. These include:

Despite the popularity of the NA engine, this technology has been made more efficient over time with the widespread pairing with either turbocharging and supercharging. Please, read on!

When was turbocharging invented?

Turbocharging was first patented by Dr Alfred Buchi in 1905 for a marine-based engine, however we once again refer to Gottlieb Daimler who was one of the first to experiment with forced induction to work with internal-combustion engines.

By 1918, a turbocharger had been developed for use in the V12 Liberty aircraft. It was then the trucking industry that brought the turbocharger into the modern day (with the invention of turbo-diesel engines), with passenger vehicles not receiving a turbocharged engine until the 1960s.

The oil crisis in the 1970s brought in a greater use of the turbocharger, as it was key to making an engine feel like it had the power of a larger naturally-aspirated engine but also greater efficiency and far superior fuel economy – all without having to use a big ol’ V6 or V8.

Turbochargers are now commonly used on nearly all new cars (or at very least sportier equivalents in higher grades) and have been incorporated with electric power to create very efficient combustion engines of the modern day.

How does turbocharging work?

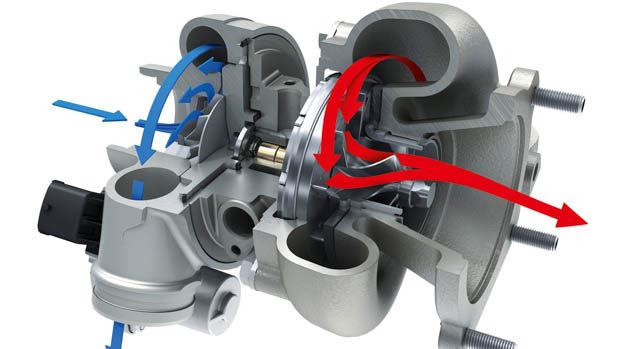

Think of a turbocharger like a giant blower, pushing air into the cylinders. In basic terms, a turbocharger is not operated because of a driven pulley or belt (like a supercharger would), but instead by using the kinetic energy created by the exhaust gases.

When the driver puts their foot down on the throttle, exhaust is created, which then spins a small turbine inside the turbocharger to suck compressed air that has been cooled (through an intercooler) into the engine.

It’s kind of genius, really. Almost any car can be turbocharged and can be twin or even quad turbocharged, too. The more turbos generally means that there will be less delay between you pushing your foot to the floor and the turbocharger firing up and boosting the engine.

That is called turbo-lag, and it’s a problem you won’t find in a naturally-aspirated or even supercharged engine. Because there is a slight delay in building boost, the engine is at a slight disadvantage to a naturally-aspirated car at the start.

Manufacturers such as Porsche and BMW have worked out a way to make their turbocharged engines feel naturally-aspirated and very, very responsive, however nothing can truly feel like a naturally-aspirated engine.

Which cars have a turbocharger?

Most manufacturers offer vehicles today with a turbocharger fitted. Some highlights on sale in Australia today include:

Where or when was it invented?

Twincharging was invented by Lancia during the World Rally Championship for its Delta rally car, combining a turbocharger with a supercharger. The main aim was to compensate for each of the chargers’ losses or disadvantages.

The supercharger was to aid response from the lack of response from the turbocharger and the turbocharger was to aid low down shove that a supercharger does not inherently carry.

How does it work?

A common arrangement of twinchargers is a ‘series’ setup which works when a compressor’s (turbo or supercharger) output feeds the inlet of another. The supercharger provides near-instant manifold pressure, eliminating the dreaded ‘turbo lag’.

Once the turbocharger has reached operating speed, the supercharger can either continue forcing the pressurised air to the turbocharger inlet (yielding elevated intake pressures), or it can be bypassed using a bypass valve.

What cars have it?

Twin-charging has been popular in both Volkswagen Group and Volvo products such as the Volkswagen Polo 1.4-litre engine and the Volvo 2.0-litre engine. The Volvo engine could produce up to 270kW of power with this combustion configuration.

Another company that has used the twincharger setup is Jaguar Land Rover with its 3.0-litre straight-six engine.

What about other charge systems?

Twin-scroll turbocharging has helped to reduce lag in performance cars by adding a second scroll or inlet to direct exhaust gas pulsations from each cylinder. By splitting the exhaust inlets, more energy can be used and minimises back-pressure losses and therefore improves engine response at low rpms.

Anti-lag systems can be seen as a kind of charge setup, however they mainly are created for performance gains thanks to running rich fuel timings and pumping air into the exhaust system to create the sense of no lag in a turbocharged car. This is commonly used in racing and rally cars that need high levels of throttle response.

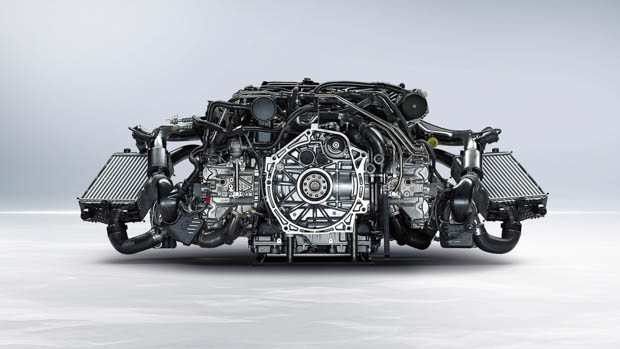

Twin turbochargers can be used in cars and can be set up in parallel, sequential and series configurations. Parallel twin-turbochargers can be used instead of a larger single turbocharger and are commonly used in V6 or V8 engines where one turbocharger can be assigned to each bank of cylinders, such as in the Mercedes-AMG 4.0-litre twin-turbo V8 engine.

Sequential turbochargers utilise one turbocharger for low engine speeds and another turbocharger for higher speeds. This setup is intended to overcome the limitations of a car running a large single turbo that requires more exhaust power to get boosting than two single turbos.

Variable-geometry turbochargers have come into existence thanks largely to diesel-powered commercial vehicles such as large trucks.

Porsche, however, has made this particular type of turbocharger well-known within the car industry. The technology works by constantly altering the size of the turbocharger at different speeds to help make the car perform more efficiently. This was first introduced on a petrol car with the 997 Porsche 911 Turbo.

Finally, a series twin-turbo setup uses the first turbocharger to compress air, which is then compressed further by a smaller turbocharger on the way to the intake manifold.

When was supercharging invented?

Long before the scroll-type turbocharger was a big deal, the mechanical supercharger was born thanks to Mr Gottlieb Daimler who received a German patent for supercharging an internal combustion engine in 1885.

But this new technology wasn’t just used for the automobile. Aircraft engines were fitted with superchargers to help allow the motor to breathe at high altitudes and during diving manoeuvres to ensure the engine did not stall. This kind of forced induction was installed in iconic planes such as the British Supermarine Spitfire and American P51D Mustang used during World War 2.

Back on land, the first production vehicle to use a supercharger was the 1923 Mercedes 1.6-litre and 2.6-litre engined cars that were labelled as ‘Kompressor’, a name which was used right up until 2012 on Mercedes-Benz models.

How does supercharging an engine work?

A supercharger works by forcing compressed air into the air intake plenum and then the pistons of an internal-combustion engine. The supercharger is powered via direct-drive, usually through a pulley connected directly to the crankshaft of the engine.

Some of the first superchargers developed were the Roots-type superchargers which basically use two rotating lobes to force air into the engine. However, many superchargers of today are twin-screw type which are, as the same suggests, two screws intertwined to suck air into the engine.

Which cars have a supercharger?

Supercharging is becoming less and less common as time goes on in the motoring industry, however some new cars, mainly of the American performance variety, are available with a supercharged engine.

These include:

Upsides/downsides of supercharging

The main upside of a supercharged engine is that it offers much better throttle response and control thanks to instant power delivery. A supercharger doesn’t need to ‘spool up’ in the same way that a turbocharger does, so this is a big benefit that a turbocharger can’t match.

The downside with supercharging is that the supercharger is powered directly by the engine via a chain or belt. This means that the crankshaft is forced to work harder than it usually would in a naturally-aspirated or turbocharged car.

The benefit of a turbocharger over a supercharger is that it does not put additional strain on the combustion process and instead uses the end product (exhaust) to make the system work.

Latest guides

About Chasing cars

Chasing Cars reviews are 100% independent.

Because we are powered by Budget Direct Insurance, we don’t receive advertising or sales revenue from car manufacturers.

We’re truly independent – giving you Australia’s best car reviews.